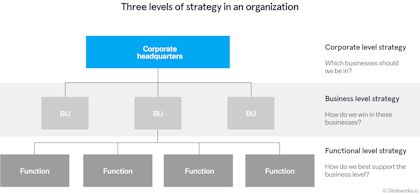

To learn more, take a look at our post on the three levels of strategy or our post on the nature of strategy and what it is not. You can also read this excellent article by Michael Porter on the distinction between corporate and business-level strategy.

Corporate strategy in a nutshell

A diversified company is made up of a number of distinct businesses (or business units) as well as a corporate headquarter. These parts together form an enterprise.

Corporate strategy, in a nutshell, has one single purpose: ensuring that the whole equals more than the sum of its parts.

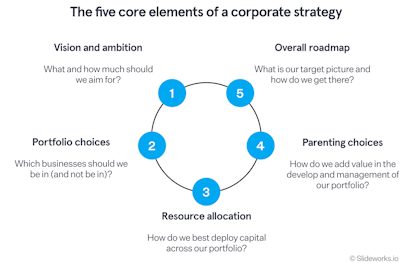

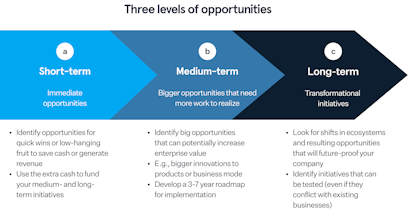

In other words, the goal of a corporate strategy is to create a roadmap for sustained value creation across its entire portfolio. This means both enabling each business to fulfill its strategic potential and deciding where, when, and how to shift the entire portfolio in a new direction.

What is corporate level business strategy?

Corporate strategy goes by various names, such as portfolio strategy, organizational strategy, or simply company strategy.

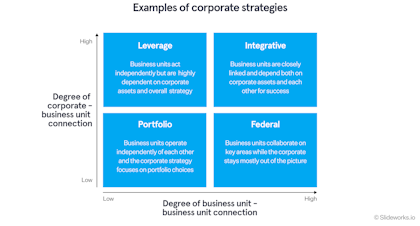

In a standard organizational structure, business units (also called strategic business units) function as semi-autonomous entities, each focusing on its own markets, customer segments, and value propositions. These units collectively constitute the corporation and are coordinated by a central corporate head office. The degree of coordination depends on the type of corporate strategy you choose (see the section on Examples of corporate strategy further down).

Renowned strategy scholar Michael Porter defines corporate strategy as…

A diversified company has two levels of strategy: business unit (or competitive) strategy and corporate (or companywide) strategy. Competitive strategy concerns how to create competitive advantage in each of the businesses in which a company competes. Corporate strategy concerns two different questions: what businesses the corporation should be in and how the corporate office should manage the array of business units.

Corporate strategy is what makes the corporate whole add up to more than the sum of its business unit parts.

The corporate strategy serves as the all-encompassing strategy for the entire organization. It establishes boundaries and provides guidance for the strategies of individual business units. In addition, it allocates and coordinates resources across the group to both enable each strategic business unit to reach its full strategic potential, and to add or divest new businesses that will bring the entire organization to the next step of growth. Finally, a corporate strategy also lays out how to communicate to external stakeholders, especially with public companies where TSR and stock price are important factors.

Ideally, the corporate strategy comprises a set of objectives and actions designed to empower the group to generate value that exceeds the cumulative impact of its individual components.

The primary objective of a corporate strategy is to formulate a roadmap for consistently generating value throughout its entire portfolio.