Strategy is a very broad term and can mean a lot of different things depending on who you talk to. In this article, we will cover strategy through the lens of management consulting based on our experience at Bain, BCG, and McKinsey.

In this context, there are three main levels of strategy in an organization:

The corporate level strategy that focuses on the company as a whole and is the overarching strategy.

The business level or business unit strategy that focuses on a specific business unit within the broader organization. If you’re a small organization, then corporate strategy and business unit strategy are often fused together in a single cohesive business strategy.

The functional level strategy that focuses on a specific functional area or team, which is often closer to a tactical plan. You can argue that functional strategy is not actually a strategy level in itself, but for completeness, we include it here.

In the following we will cover what these three levels of strategy mean and how they are different.

Apart from these three core levels of strategy, there are various permutations and subcategories of strategy like digital strategy or growth strategy. These are not part of this article but in essence follow the same principles of a corporate or business unit strategy, where you create a plan within a context.

You can also take a look at our blog post “5 Key Elements of a Successful Strategy Document” to get tips and tricks on creating a strategy presentation.

What is Corporate Strategy?

Corporate strategy has many names, including portfolio strategy, organizational strategy, or simply company strategy.

A typical organization is made up of business units (or teams in a smaller company) that act as varying degrees of stand-alone entities. Together, the business units form the corporation, unified by a corporate head office.

The corporate strategy is the overarching strategy for the entire organization. It sets guardrails and direction for business unit strategies and should ideally be a set of objectives and actions that enable the group to create more value than the sum of its parts.

The famous strategy scholar Michael Porter defines corporate strategy as

A diversified company has two levels of strategy: business unit (or competitive) strategy and corporate (or companywide) strategy. Competitive strategy concerns how to create competitive advantage in each of the businesses in which a company competes. Corporate strategy concerns two different questions: what businesses the corporation should be in and how the corporate office should manage the array of business units.

Corporate strategy is what makes the corporate whole add up to more than the sum of its business unit parts.

The ultimate goal of a corporate strategy is to create a roadmap for sustained value creation across its entire portfolio.

For an in-depth discussion on corporate strategy, see our article "Corporate Strategy: What Is It and How To Do It (With Examples)".

There are five key elements of a corporate strategy:

1. Setting a unified vision and ambition

Your corporate strategy should begin by defining your organization’s mission, vision, and purpose. This provides a unified direction for all subsequent choices in both your existing portfolio of businesses and in where, when, and how to invest in growth or divest assets.

Furthermore, your corporate strategy should include specific goals, both quantitative (externally or market-driven) and qualitative (internally or company-driven), to guide the organization and energize stakeholders.

2. Making portfolio choices

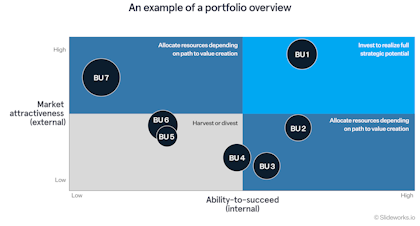

The second key element of a corporate strategy involves conducting a comprehensive portfolio review. This review assesses all the business units, products, or brands within the organization. It determines where to focus efforts, which industries and markets to enter, and how to diversify the product and service offerings.

The goal of your portfolio review should be to identify businesses or assets with the highest strategic potential, either as stand-alone entities or as part of the larger organization. This means making hard decisions on where to acquire, divest, and transform the portfolio, and importantly, how to allocate resources at a high level across business units (i.e. which businesses do you invest in for innovation and growth versus which businesses should be optimized for efficiency and cash-maximization).

While the allocation of resources is a topic addressed separately in the next section, the portfolio review serves as a blueprint for determining which businesses or assets should be allocated resources.

To conduct a portfolio review effectively, you need a deep understanding of each business unit's current potential and future opportunities and threats, often informed by their individual business unit strategies. You can see more on this under the Business Level Strategy section further down.

The results of the portfolio review are typically presented in a matrix format, with one axis evaluating a business unit's current ability to grow or succeed internally and the other axis assessing the market conditions and external factors affecting the business unit.

3. Allocating resources

The third component of a corporate strategy involves how to allocate resources, particularly financial decisions related to investments in acquisitions, balancing investments with shareholder returns, and distributing resources among various business units or product lines.

For public companies, this typically entails three primary financial considerations:

A. Capital structure

Capital structure is defined as a company’s mix of debt and equity. On a corporate strategy level, you need to decide how much funding will be allocated across your portfolio and which financial guardrails you want to put in place for that funding.

B. Capital deployment

Once the amount of available funding and associated guardrails are in place, the corporate strategy should allocate that funding across portfolio businesses according to the outcomes of the portfolio review. This typically means investing and acquiring aggressively in businesses or assets that have a lot of strategic potential, and minimizing costs through efficiencies and other optimizations in businesses that have less of a gap to their full potential.

C. Capital markets communication

If you’re a public company (or with external stakeholders like VC funds), then the final piece of your financial strategy is summarizing your other choices in a compelling story that makes strategic sense and should hopefully push your external value up.

4. Maximizing parenting advantages

The fourth element of a good corporate strategy is a thorough discussion of how the corporate entity can maximize each business unit (i.e. making the whole more than the sum of its parts) and consequently what role or form the corporate parent should take to achieve that.

This falls into three categories:

- Best portfolio operator: How can you from a corporate side facilitate cooperation between business units and portfolio companies? Which synergies can be leveraged? How can you share costs? Which customers can be cross-linked?

- Best owner: How can you add differential value developing and managing the portfolio? How can you best capture value across the different businesses and allocate this to lift the entire portfolio? Which acquisitions and divestments should you make to bring the full organization to a better value creation point?

- Best culture champion: How can you create energy and mobilize latent talent across the organization? Which values and principles should you instill, and which people should you hire to lead each business on this path?

5. Creating the overall roadmap

The fifth and final element of a corporate strategy is laying out an overall roadmap for sustained value creation.

This can be done in more or less detail depending on how involved the corporate parent is in each business unit strategy. But a well-known schema for roadmaps at this level is to break them down into three time horizons: short-, medium-, and long-term.

This typically corresponds to three levels of opportunities: a) immediate opportunities, b) bigger opportunities that need more work to realize, and c) long-term, transformational initiatives and ideas.

Each opportunity should be broken down into initiatives and actions and put together in a cohesive roadmap. The level of detail will become less and less the further out in time the roadmap goes.

What is Business Level or Business Unit Strategy?

Business level strategy is what most people think of when you mention the word strategy.

Business unit or business level strategy focuses on how to create a competitive advantage for that specific business in their specific market. You can also call this a business model strategy, as it often examines the elements of a business model as exemplified in e.g., the Business Model Canvas.

There are many ways to approach business level strategy and each method has its own merits. We would recommend not thinking too much about following a rigid framework, but rather working through your particular strategy in the way that seems most logical to you.

In addition, it helps to distinguish between the process of creating your strategy and creating your subsequent strategy presentation that summarizes that strategy.

Here, we will first go over a simple approach to creating a business level strategy and then briefly touch on translating that to a cohesive strategy document. For more information on how to write a strategy presentation and a template for creating one, see our Business Strategy template.

Defining the starting point

The first step of any strategy process is understanding your point of departure. Without a solid view on your starting point you’ll be operating blindfolded and not taking advantages of your current strengths nor adequately adapting to potential weaknesses or threats.

There are in general three components to creating a clear picture of your starting point and strategic arena:

A. Defining the guardrails of your strategic option space

B. Understanding your current situation

C. Mapping out your potential areas of growth

A. Defining the guardrails of your strategic option space

Before you start looking at goals and initiatives for your new strategy, you need to understand your overall playing field.

You can think of this playing field along two dimensions; Your strategic and financial degrees of freedom.

Along the strategic dimension, ask yourself questions like:

- To what extent are you playing offence (upside value creation) vs. defence (downside value protection)? And is it the right priority going forward?

- What is the right balance of growth inside and outside your core businesses?

- What is the urgency to pursue opportunities vs. managing downside risk of disruption?

- Do you need to consider radically different strategic directions, or can you stay within your current strategy with optimizations and tweaks?

- How does this fit into the overall corporate strategy?

Along the financial dimension, ask yourself question like:

- How do you define value? What is your value creation goal (and how does this fit into the overall corporate picture)?

- What is your risk appetite?

- What is your time frame?

- How much funding or cash reserves do you have to invest in new initiatives?

The answers to these questions will help you define the perimeters of your strategic option space.

B. Understanding your current situation

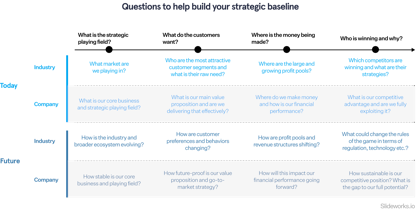

Now that you have a clear picture of the overall playing field you can maneuver in, it’s time to build a baseline of your current situation on which to base your strategy.

This means creating a data-driven overview of where you stand in terms of both your industry and your competitive position now and in the future.

More concretely, you can answer the questions outlined in the picture below:

C. Mapping out your potential areas of growth

The final piece of the puzzle when defining your point of departure is understanding your potential areas of growth in terms of new opportunities, or areas where you’re losing market share or revenues in an otherwise stable or growing market.

This can typically be divided into two main buckets where bucket A means optimizing your current business and bucket B means finding new pools of revenue/experimenting with new business models.

In consulting speak, you’ll often hear the terms grow (or reinvent) the core and new growth engines to describe buckets A and B, respectively, so we’ll use the same terms here.

Growing (or reinventing) the core

Once you understand your current situation and your strategic arena it becomes easier to identify ways to grow your core. Growing your core in basic terms means doing your current business better. This can be done with classic competitive levers like being cheaper than competitors, becoming more sustainable, optimizing your current processes and value chain to become more efficient and faster, expanding your products and services to include add-ons or adjacent value propositions etc. These are all examples of business level strategies that you can use to create a differentiated, competitive advantage.

You can also talk about reinventing your core, where you typically stay within the broader boundaries of your business model in terms of customer segment and industry/area but completely transform the way you serve your customer needs to protect or increase your share of the profit pool (see e.g., this McKinsey article for inspiration).

A great, non-digital example of reinventing the core is the global beer brewery Carlsberg, which has effectively moved into both the artisanal and alcohol-free beer markets in addition to their traditional beers.

Unlocking future growth

However, growing your core business is just one way to create value. The second and equally important bucket is the new growth engine bucket.

This essentially means creating new sources of revenue for your business by creating/moving into entirely new products or services (like Amazon’s AWS business).

There are a multitude of great articles and inspiration videos on creating new growth engines and too many . See e.g., this Harvard Business Review article for a discussion on growth engines or this McKinsey article for tips on actually incorporating a growth strategy in your overall process.

Creating your strategy on a page

The final piece of a business level strategy is creating a strategy document that effectively summarizes the BU strategy and allows it to be easily communicated to both employees and across the rest of the organization.

Irrespective of the framework you have chosen to follow, developing a strategy document entails addressing five fundamental questions:

- What is our current situation in terms of our own performance, industry, competition, and the broader macro environment, and how will it affect us in the future? (I.e., a summary of your starting point)

- Where do we have an existing competitive edge (or high potential for one) in e.g., customer segments, markets, or geographic areas, and how can we enhance this advantage through our solution delivery, differentiation in our value proposition, and the efficiency of our go-to-market approach?

- What are our primary strategic choices required to establish and maintain these competitive advantages? How do these choices translate into strategic pillar areas and opportunities? What does success in these areas look like?

- Which strategic initiatives must be implemented to realize these choices and achieve our goals? What organizational enablers or structures are needed to support these initiatives?

- How do we integrate all of this into a comprehensive plan to ensure we have the appropriate resources and governance in place to drive strategic change effectively?

For most businesses, strategy essentially means focus – aligning their business model with customer value, competitive differentiation, and improving return on investment. Crafting a strategy often involves deciding what activities to forgo in order to allocate resources to more impactful initiatives. This process also highlights strengths and weaknesses within the business model. By concentrating on specific customer segments and aligning various components, companies can tap into their growth potential.

See our blog post “5 Key Elements of a Successful Strategy” for more practical tips or download our full Business Strategy template to get a jumpstart on your own strategy presentation.

What is Functional Level Strategy?

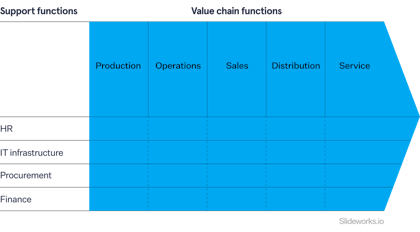

The third and final level of strategy is functional strategy. Functions in an organization typically refer to the teams that are organized around a specific operational element of the business, or individuals in multi-function teams that have specific roles.

You can think of functions as both support functions that run across an organization, e.g., HR, procurement, technical infrastructure, and as functions related to the specific parts of the value chain, e.g., sales, marketing, customer service.

Taken together, the collaborative work of the functions are what produce and deliver the value proposition and go-to-market.

The goal of a functional strategy is to best support and enable each business unit within the organization to achieve their strategic potential, while making sure the overall portfolio prioritization is adhered to.

Put simply, your functional strategy level is the strategy that guides the daily efforts of your employees and ensures your organization stays on the right path. Without well-defined functional strategies, your organization can quickly lose momentum and become stagnant while competitors forge ahead.

For larger organizations, it becomes crucial to consider how different functions can contribute to growth and collaborate effectively while adhering to the corporate strategy. Each function or department, including marketing, finance, IT, and operations, has its own set of goals and responsibilities. Establishing visible functional strategies that are consistent and align with the overarching corporate strategy significantly increases the likelihood of success.

Depending on the way your organization and business units are structured, the functional level strategy is sometimes closer to a tactical day-to-day plan (focused on execution rather than direction-setting). Regardless of whether this is the case, is it still important to have a systematic planning process in place for functional strategies to make sure the entire organization is aligned and consistent across strategic ambition, governance, and KPIs.

Functional level strategy examples

Depending on how your company is organized, examples of functional strategies could be:

- HR strategy: HR strategies can range from simple “center-of-excellence”-type strategies where you provide the best systems and processes for businesses to use in their own people departments, to detailed complete HR strategies around recruitment, training, performance management, compensation, retention etc.

- Marketing strategy: Marketing strategies typically focuses on planning and executing marketing campaigns including identifying and understanding target customer groups, understanding the value propositions, and creating and running the actual campaigns or efforts to gain more customers. The larger an organization becomes, the more likely it is that marketing is kept within each business individually.

- R&D strategy: Depending on the industry, you may have a need for a distinct R&D strategy to help determine how resources are invested in creating new products, technologies, and services.

- IT strategy: Oftentimes it makes sense for an organization to have a shared technology infrastructure. Here, and IT strategy means planning for and managing the organization’s technology resources and includes decisions on which systems to use, how to store and manage data, how to address cybersecurity etc.

- Production strategy: You may also have a setup where a shared production facility and infrastructure are most beneficial. In this case, a production strategy often sets goals and initiatives around supply chain management, production planning, quality control, logistics, and inventory management in a way that best support the business units’ strategies.

These are just a handful of examples. Others could be strategies around distribution, sales, partnering or more. It all depends on how big and decentralized your particular organization is set up.

If you don’t have specific functional strategies due to size or structure, then they’ll often be implicit in the business level strategy and the individual functional teams will have KPIs and tactical plans related to the business unit strategy.

What are the differences between Corporate, Business Unit, and Functional Strategy?

Corporate strategy is about your portfolio as a whole, deciding which businesses to be in, how to allocate capital, and how shareholders are rewarded.

Business unit strategy is the classic business model strategy of creating and maintaining a competitive advantage in your specific market. As mentioned, depending on the size of the organization, corporate and business unit strategy may be one and the same.

And finally, functional strategy is the operating level of the organization. Here the strategies are centered around how to best support and enable each business within the portfolio to achieve their strategic potential as outlined in the overall portfolio prioritization.

Building and executing a succesful strategy requires you to make sure all three levels of strategy are aligned and work in tandem. You may not necessarily need each business unit strategy to be mutually exclusive or for business units to have completely different markets etc. (in fact, sometimes you may want to run somewhat competing businesses to both run and reinvent your overall competitive advantage at the same time), but you do want to make sure that both your corporate strategy and functional strategies don’t undermine the efforts of the business unit strategies that are closest to customers and bring in revenues to the organization.

By creating consistent strategies on all three levels you’ll be able to better gain and sustain your overall competitive position and future-proof your organization.